The Chinese artist-activist Ai Weiwei has shown his work around the globe. His creations mostly are large in scale and ambitious; looming tree trunks, reconstructed Chinese furniture, giant murals made of LEGO, marble baby carriages. Throughout, there is always a critical political sub-text and, in my view, beauty.

In 2011 the Chinese government detained Ai for three months and it was not until July 2015 that they allowed him to travel out of the country for the first time in years. Where did this activist artist go, once set free from his motherland? Right into the thick of international strife, to document Middle Eastern refugees fleeing towards Europe.

Ai Weiwei’s concurrent shows in New York’s Lisson Gallery (504 West 24th street) and downtown at the Deitch Project (18 Wooster Street) are located 3 miles apart, but it is worth seeing both shows if you happen to be in New York City.

The work entitled “Laundromat” at the Deitch Project on Wooster street is both alarming and arresting. One needs some preparation before entering the gallery.

In the Spring of 2016 Ai and his team of assistants documented, interviewed and filmed the refugee crisis as men women and children from the war-torn Middle East swelled at the border between Greece and Macedonia in the tiny village of Indomeni. Over 8,400 refugees were evacuated to different camps all over Greece. This is explained on two separate wall panels in the gallery.

After refugees dispersed and left the camp, their discarded clothing was left behind. Authorities planned to bulldoze. The artist took action and collected thousands of the discarded personal items from the camp, and transported them back to Berlin, Germany, to assemble in his studio. Here, they were carefully washed, pressed and categorized by type.

The final product reveals itself at the Deitch Project’s newly opened space. Here Ai Weiwei combines photography, video, social media and over 2000 garments, to document the crisis at Idomeni.

The fluid feeling of dislocation is recreated as you approach the street-level gallery. The expansive space is filled with dozens of metal coat racks. They are arranged in orderly and intersecting rows that occupy the entire ground floor level. On closer inspection, each rack is organized: Childrens’, Men’s, Women’s, Baby-pants, Outdoor jackets.

The labels on the racks are cardboard and handwritten, and each individual garment is numbered in a pink or turquoise tab. I am struck by an infant’s shirt in baby blue that reads “Time to recharge my batteries!!”

At the back of the gallery is an aerial video wideshot of the spreading camp, then videoshots of border authorities in dark uniforms dispersing tear gas and rubber bullets into the protesting crowd. Someone off camera says in broken English (sarcastically) “Welcome to Europe.” Children lift used tear gas canisters, another shot shows an inconsolable infant crying. The fear and discomfort is palpable.

In stark contrast, a later scene shows Ai and his team in their tidy Berlin studio. An assistant irons a pair of trousers. There is a close-up of a hand wiping clean the stitching of a child’s shoes. A hand uses a tooth brush to clean the treads of an adult boot.

In the gallery you can see the product of these cleaning labours set out before you. Actual shoes are assembled in 20 rows, organized in categories: flip flops, rubber boots, etc. In the centre are baby and toddler shoes.

The straight rows of shoes and clothing create a semblance of discipline. Ai gives order and consideration to the belongings of people in disarray. Taking care of their material belongings in their absence, he makes us question our own responsibility to these people in despair.

In accompanying literature Ai explains he is drawn to the subject of refugees, as his family was sent to a labour camp as a child with only a few of their personal possessions. “I know what it is to be viewed as a pariah, as sub-human, as a threat and danger to society.”

In addition are walls of photos, vinyl stickered from the floor to the ceiling, and excepts from Twitter, WhatsApp and internet news items. You are immersed in the refugee crisis with both images on the wall, text at your feet, and the tangible hanging clothing and lined-up shoes. The gallery assistant explains this display is to be considered as a whole. These are not separate pieces of art. And no, nothing here is for sale.

The theme of displacement continues at the Lisson Gallery, a 20-minute cab ride away to Chelsea, at the show entitled “Roots and Branches”. Here, in contrast to the Deitch Project, you will find items for sale (starting at 6 figures). Throughout the space, 7 cast-iron tree trunks and roots, measuring about 16 feet in length, are scattered. Rich rust colours suggest a natural wood. On closer inspection, you realize these pieces are metal.

These sculptures are ominous and looming. Their upward reaching tendrils suggest a lightness, reaching to the sky, and yet we know they are heavy and earthbound in their iron material. These pieces are a magnificent presence in their own right, yet it is the black and white wall paper lining the gallery’s West wall that steals the show,

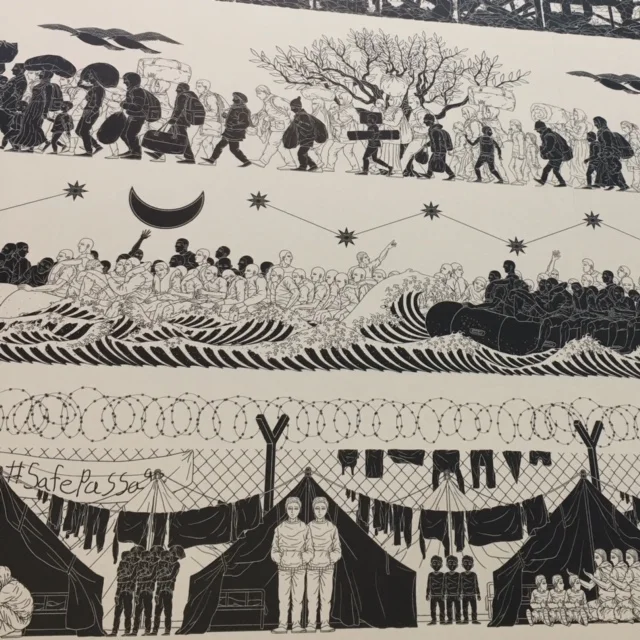

As opposed to the sculptures that can be examined at a distance, one must come close to look at the wallpaper. It shows what looks like ancient Greek warriors, but then you see these profiled figures are donning 20th century assault riffles. Conflict in the streets, barrages of police, helicopter assaults of bombed-out buildings, families walking through orchards, people on small vessels with rolling waves, refugee camps with small children in women’s arms. Women wear hijabs. In all images the faces are unsmiling, eyebrows indicating various degrees of strain.

The patterns and detail of lines give a flowing rhythm to the work, a feeling of harmony. But the storyline is that of strife, suffering and civilian flight resonating with the headlines of the refugee crisis in the Middle East. Ai straddles traditional modes of representation to show us contemporary struggle.

The wallpaper at the Lisson New York illustrates the artist's earlier studies at the Idomeni camp, as shown at the Deitch Project. The two shows connect and should be seen together.

There is a third gallery that exhibits Ai Weiwei - the Mary Boone Gallery, a show entitled “Trees and Branches.” A giant 25-foot reconstructed tree looms large and there are self-portraits in LEGO. These works are impressive and successful, although they do not document the refugee situation.

If you are a fan of the artist, and have time, I urge you to visit all galleries. If not Lisson Gallery and the Deitch Project should be your focus.

Exhibits at all the galleries end December 23 2016.

LISSON GALLERY NEW YORK

Ai Weiwei 2016: Roots and Branches

504 West 24th Street, NY NY 10011

Phone: 212-505-6431

DEITCH PROJECT

Ai Weiwei Laundromat

18 Wooster Street, NY NY 10013

Phone: 212-343-2700

Tanya Rulon-Miller is a freelance journalist

Tanya can be followed on instagram as ttrrex