The move from real life art encounters to online art encounters has been both inspiring and overwhelming. In the last three months, I have virtually been to Giotto’s Scrovegni chapel and to artists’ studios; I have shopped (but not bought) online at Frieze New York and watched specially released artist films. My favourite was a ‘screen walk’, organised by The Photographer’s Gallery, where US-based photographer Penelope Umbrico took us on an exploration of the images on her computer: scanned photos from online marketplaces which she uses in amalgamated collages. These tiny peeks into people’s homes, and by extension into Umbrico’s computer, took on a new meaning now that most of us are stuck at home.

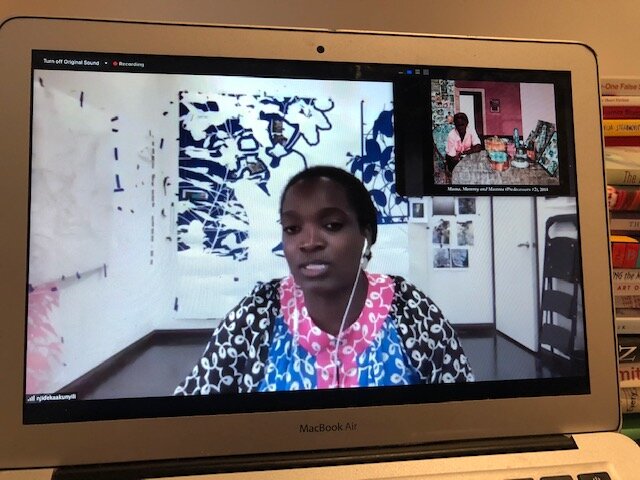

Amongst the cacophony of artworks and initiatives, two events stood out for me, both attended this week. The first one was a Zoom artist talk with Njideka Akunyili Crosby organised by the Brooklyn Rail, with a staggering 387 participants from all over the world. I have always been a huge fan of Akunyili Crosby – see my blog on the artist last year; her monumental paintings with deep, saturated colours mixed with transfers of images from African life veer beautifully between intimacy and globalism (Akunyili Crosby uses the word ‘transcultural’ to describe this crossover theme).

The most moving part of the talk, especially in the light of recent events, was when Akunyili Crosby told us about her experience of being a black undergraduate art student at Yale. She still gets tears in her eyes, she tells us, when she thinks back to that time. “In my classes, I would say things and get no reaction. Then a white person would say exactly the same and get all the attention. So I just decided to stay silent.” Fortunately, one professor at Yale, Hazel Carby, recommended she go to Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania for her doctorate, where she had a much better time. The Zoom Chat loads with comments from people relating similar experiences. It gives the artist talk a warm feeling of community.

My daughter Isabella in front of Mama, Mummy and Mamma, at MOCA LA (2019)

Akunyili Crosby comes back to the invisibility of black people later in the talk. Interviewer Jason Rosenfeld asks her how she experienced the change from showing works on paper in museums, to showing works on giant billboards – they have been installed outside The Whitney and MOCA, amongst other places, and onto the side of The Hayward and at the entrance of Brixton tube station in London. “I hesitated about the billboards at first, because my work is so deeply seated in materiality, but then I thought about all those new audiences”, she says. “People who would not normally enter the barrier of a museum.” She quotes George Gerbner: “Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation”.

In art-historical terms, Akunyili is inspired by a broad range of artists, from black artist Carrie Mae Weems to Danish painter of still interiors Vilhelm Hammershoi to the palette of Edgar Degas, a mixing of styles and influences that loops back to her transcultural theme. When she first encountered Kerry James Marshall’s portrait of a black female painter holding a giant palette with the colours of the pan-African flag at Yale University Art Gallery she was awestruck. “This woman was so confident and she was looking at me, like, ‘Yes, this is my space!’ And the work was done in acrylic. Luminous painting can be done in acrylic!”

Akunyili Crosby’s enthusiasm is contagious. But she never lets us forget that we have to evict racism from the inside, from every pore of our global bodies. The shocking lack of representation of black people is something the art world has only recently started correcting, and there is a long way to go.

Another artist who is re-addressing the imbalance of representation is Gisela McDaniel. Gallerist Pilar Corrias, who has just started representing McDaniels, interviewed her via Zoom in her studio in Detroit. McDaniel is a Diasporic indigenous Chamorro artist (her family is from Guam) and she works primarily with womxn who identify as indigenous, multiracial, immigrant, and of colour. She paints portraits of those who have experienced gender-based sexual violence, with the aim of helping them heal. “Surprisingly”, she says, “many women I interview like to be painted naked. It is a means to reclaim the power in their own bodies.”

There is a depth and aliveness in the portraits achieved through layering: branches of plants are thickened with fluorescent paint, wiry lines criss-crossing the canvas or sprouting out like coloured banana peels. The person’s most loved objects are added to the portrait: in one painting, part of a tie-dye t-shirt jumps out of the canvas, in another, a portrait of her mother, McDaniel has glued on her mother’s jewelry. “They have their energy with them”, she says. Most of McDaniels women wear masks with stripes in bright colours like camouflage. “The mask is a mesh between the subject and the gaze” Mc Daniels explains. The care for her subjects is truly moving.

Look Back, Look Forward, 2020 (Image: Artsy)

Further enhancing the immediacy of the portraits is their audio component. McDaniels records each conversation: between artist and sitter, or multiple sitters – and these recordings become part of the works. We hear a short audio on Zoom that belongs to her work Look Back, Look Forward. “Racism just violates me constantly” is said twice, and if we were in a real space I am certain you would be able to hear a needle drop.

Like Akunyili Crosby, McDaniels is equally inspired by art history, mostly by Paul Gauguin. Gauguin himself, of course, does not have the best reputation when it comes to treating women, starting a family in Tahiti with an underaged girl, leaving her to brag about his contests in Paris, coming back to Tahiti to use other women’s bodies. But my feeling is that McDaniels is able to look past Gauguin’s ego to care about the women he painted. She takes an interest into their world, an indigenous culture similar to her own Chamorro culture. I imagine McDaniels traveling back in time to Tahiti, sitting down with Gauguin’s women, asking them what they really felt. Truly listening.

Both Anyukili Crosby and McDaniels are claiming their space and taking what they want from history, just like white people have been doing all along. It’s about time.

You can watch Brooklyn Rail’s artist talk with Njideka Akunyili Crosby here.

View Pilar Corrias’ website for more information on Gisela McDaniels