When I think of interiors in Western art history, I think of the contemplative quietude of Vermeer or Chardin. I think of the frivolous burst of colour in the scenes of Bonnard and Vuillard. Or, more recent, the stark sunlit rooms of Hockney. Njideka Akunyili Crosby, born in Nigeria and living and working in LA, has burst onto the art scene in a few years’ time to become one of the leading artists of today. Her main subject: interiors.

Akunyili Crosby’w work, a combination of painting, drawing, and photography transfers, has lit up the side of buildings like the Hayward Gallery in London and the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA. At Frieze Art Fair, her work Mama, Mummy and Mamma (shown by Victoria Miro Gallery) was the largest and the most expensive piece of the contemporary section, snapped up by a major museum on the first day.

Two Akunyili Crosby exhibitions are currently on view across the pond, in Forth Worth, Texas and London (my home state and my home town, as it happens). The beautiful and underrated Modern Art Museum Forth Worth, a large concrete and glass building half an hour outside Dallas, has devoted two large rooms to six monumental works on paper. London’s National Portrait Gallery focuses on a selection of smaller works that are part of Akunyili Crosby’s ongoing portraits series of Nigeran youth.

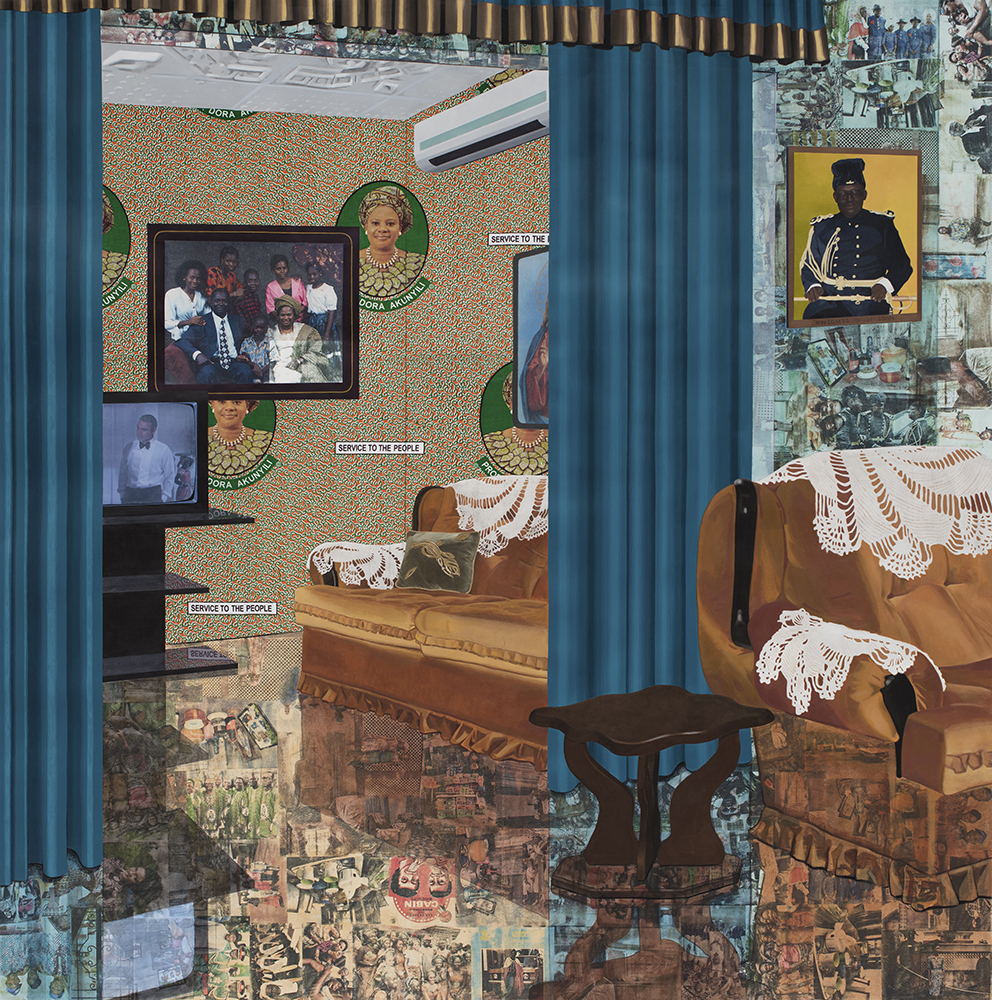

The Modern interestingly presents three pairs of interiors: one set in the artist’s birth country Nigeria, the other one in her adopted home town LA. The African rooms are more traditional. In Home as you See Me, we peek into an interior that is almost life-size. Colourful wallpaper holds family portraits, most notably of the artist’s mother, Dora Akunyili, who was a respected African politician. There are worn, brown sofas with lace covers. Heavy velvet curtains in blue open onto a back room containing an old model air-conditioning unit and an old tv set. The tv is showing Sean Connery’s James Bond.

Home: As You See Me , 2017. Acrylic, transfers, colored pencil, collage and commmorative fabric on paper, 72 x 60 in

What is maybe most striking about the interior is the floor. Using a process of transfer, Akunyili Crosby renders hundreds of small photographs taken from Nigerian society magazines. The floor looks almost transparent, yet the faces on the photographs are clearly visible. It is as if the artist literally imprints black culture onto the room.

The act of transference has an even stronger impact in Akunyili Crosby’s LA interiors. In Dwell: Aso Ebi, the artist herself inhabits he interior, sitting on a chair looking down on her elegant feet in blue tights. Her dress is a brightly coloured geometric design, as if she is comfortably wearing a Modernist painting. The wallpaper’s design looks contemporary, but it also features repeated portraits of her mother Dora as a queen-like figure (and, notably, chickens). The straight lines of the furniture and walls contrast with the dark foliage outside the window and the large portrait of the artist’s parents in African dress.

Dwell: Aso Ebi, 2017. Acrylic, transfers, colored pencil, collage, 72 x 60 in

There is a cacophony of textures and colours at play here, as well as a complex layering of references. From the rich depth of the woman’s face and her legs to the shiny top of the dining table; from the bright yellow of the clothing to the midnight-blue of the tight-cladded feet with a zing of pink: Akunyili Crosby shows complete control over her material. All her works are on paper, which further enhances their directness. The surfaces of the photographic transfers are neat and precise. There are paintings inside paintings, photographs over photographs, a family portrait inside a self-portrait. The mood is at once highly traditional and incredibly contemporary. It is as if African history is smoothed over the shiny stark features of the Californian room.

Architecture, interior decor, photography and paint all vie for our attention. But nothing disturbs the harmony of the whole. I am reminded of Matisse’s mastery of flat space and his clever blending of the abstract and the decorative a hundred years earlier. But unlike Matisse, Akunyili Crosby’s works have the added intimacy of people, deeply involved in their own thoughts, wonderfully contemplative.

As We See You: Embarassment of Riches, 2017

By blending African, European and American cultures and histories, Akunyili Crosby captures the complexity of our times. She layers images and references without hierarchy or judgment. A smaller work, titled As We See You: Embarassment of Riches, shows an interior with an extravagant Thanksgiving table , containing pumpkin pie, bowls of check-mix and smarties. In the ornate mirror we see a black woman in a fashionable dress, looking at the still life with an uninterested gaze.

Or is she? On closer inspection we can make out two ‘blackamoor’ serving trays, disturbing decorations that trivialise the history of slavery in America. It is an understated but urgent reminder that we can never escape the past.

One of the most pressing topics of the twenty-first century is identity. The personal is political. Other black artists have addressed the subject of interior space as a window onto identity: Toyin Ojih Odutola’s fictional aristocrat families in lavish interiors, or Mickalene Thomas’ glimmering spaces, collaged with bold fabrics and glitter beads. But it is almost as if Akunyili Crosby’s works don’t have to prove anything. Her works are still. Akunyili Crosby’s people sit confident and calm, completely at ease in a complex world. And maybe that is the ultimate luxury of life: the possibility to simply enjoy the everyday, without worry. Akunyili Crosby celebrates the power that comes from being truly at home.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby,, Counterparts, The Modern Art Museum, Forth Worth, Texas until 13 January 2019

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, The Beautiful Ones, National Portrait Gallery London until 3 February 2019

Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Adriana Varejão, Interiors, will be coming to Haus der Kunst, Munich, 29 November 2019 until 29 March 2020