From the moment I first saw Wolfgang Tillmans' work, I have been captivated. There is an urgency in his photographs that draws you in and holds you in thrall. Tillmans, born in Germany in 1968, and currently dividing his time between Berlin and London, was the first non-UK artist to win the Turner Prize in 2000. It is ironic, then, to look at the anti-Brexit posters he just designed, featuring prominently on his website. But when politics fail, there is always poetry.

Tillmans’ exhibition at Tate Modern brings together works in a variety of media – photographs, but also video, publications, curatorial projects and recorded music. Two things are immediately evident. Firstly, Tillmans seldom frames his photographs, emphasizing the immediacy of the photographic medium. His inkjet prints are often held up by pins and floating slightly off the wall. Secondly, Tillmans' photographs are hung in an un-hierarchical and unsymmetrical fashion: often slightly off-centre or in a corner, ranging in dimensions from almost wall-sized to the size of a personal photograph.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Exhibition View at Tate

It is like walking into a live photo album of our times. There are close-ups and landscapes, portraits and crowds, some attracting our immediate attention (a vibrant market square in India, an intimate close-up of a young male with a shaven head, scarcely-lit scenes of Berlin nightlife), others quietly complementing. Tillmans doesn’t shy away from the social and the political, but there are also wonderfully poetic still lives and entirely abstract compositions, in which Tillmans tests and stretches the medium of photography itself.

Tillmans is our contemporary ‘flaneur’, documenting and celebrating life in all its facets. The title of the show is 2017, and indeed Tillmans art is very much in the moment. There is a realness to his images as he approaches the world with a sense of wonder and openness.

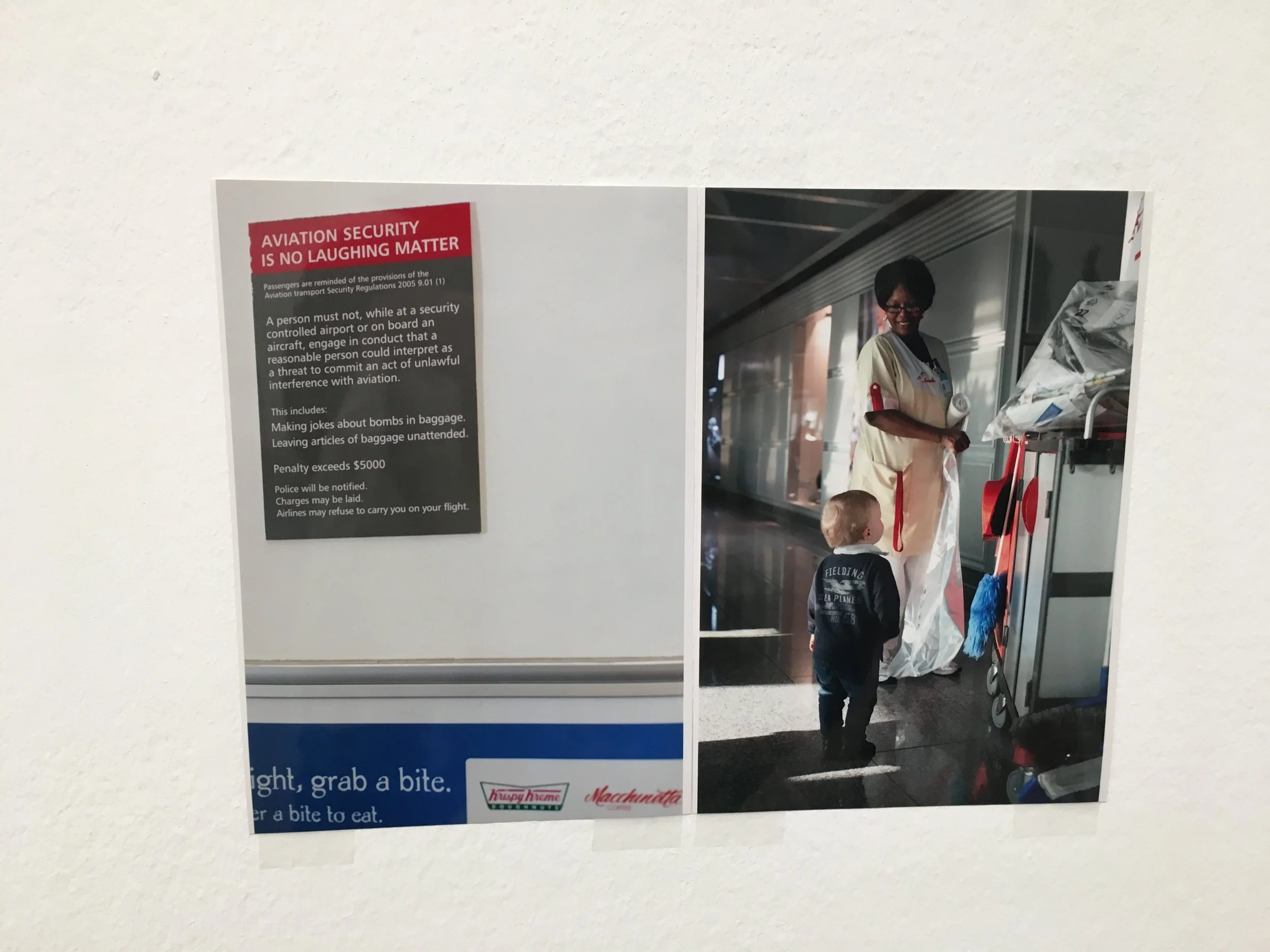

Wolfgang Tillmans' still life, and below: airport series, exhibition shots

Intimacy is made monumental, and forgettable objects take the form of icons for our everyday lives. The dark depths of fresh, green grass or the warm, glowing light of a street scene at night. An old scroll of paper left in the gutter. And the most moving still life I have seen, of a few discarded fruits in plastic.

Tillmans even finds warmth and humanity in the sterile waiting rooms of an airport. A cleaning lady, lit up like a modern-day Madonna, is watched by a boy completely unaware of the darker connotations of international air travel that Tillmans slyly references (“Aviation Security is no Laughing Matter”).

And in the midst of this cacophony are the most sublime, saturated colours, aiming straight for the heart. Tillmans’ art is direct, yet subtle at the same time. He exposes the fragility of life, whilst celebrating all its victorious moments. And there is humour, as evidenced by the two-frame film of Tillmans dancing to techno music in his underpants, followed by his shadow dancing slightly out-of-synch.

I was reminded of another great artist whose work is currently on show in London: American-born Richard Tuttle. Tuttle’s work is very different: where Tillmans documents life, Tuttle abstracts it. But both artists have the same sensitivity, the same interest in colour, and an enormous zest for life. “Art is life, in fact it has to be life – all of life” as Richard Tuttle states in one of his films on Art21, but this quote could easily have come from Wolfgang Tillmans.

Richard Tuttle’s show My Birthday Puzzle is at Modern Art, Stuart Shave’s cutting-edge gallery which recently relocated to a beautiful building in Helmet Row, Shoreditch. The works iare hung freely and at different heights across the gallery space – just like Tillmans’ exhibition at Tate. Where Tillmans occasionally ventures into abstract territory, Tuttle’s show at Modern Art is entirely non-representational. But as part of the exhibition (at least, I interpreted it that way) Modern Art has printed an accompanying text by Tuttle, in which he tries to put into words the essence of his abstract works (what he calls “a painting using its own call to Form”). The text reads like a poem:

The whole would unify,

As painting is supposed

To do, and make a pic-

Ture closer to love, truth,

Freedom. […..]

Like music,

The purely visual has

An ability to express, uni-

Que to itself.

Richard Tuttle, Pressing: Hole in the Head, VII 2015-2016. Styrofoam, metal, colored felt, heat-sensitive quilting backing, fabric paint, white glue, bond paper, enamel paint, acid-free museum mount board, metallic paper, acrylic, day-glo gouache, nails 64.8 x 92.1 x 5.1 cm, 25 1/2 x 36 1/4 x 2 1/8 ins. Courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London

Today, Pace Gallery opens The Critical Edge, a show of textile works by Richard Tuttle that forms an extension of his solo show at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2016. An avid collector of textiles, the works are assemblages of fabric that Tuttle purchased in New York and Maine, cut and sewn by hand. Although abstract and contemplative from afar, Tuttle’s works are in fact highly sensual objects that engage our senses of sight and touch. The pieces of draped fabric are pliable and respond to the surrounding environment: shifts in the air cause them to rise and fall in a manner suggestive of breathing. Because the pieces vary in their degree of opacity and transparency, they catch and release light in different ways.

Tillmans and Tuttle, both using an aesthetic of subtlety to render the everyday. Tuttle uses humble, mundane materials and elevates them into something sensual and beautiful; Tillmans captures the small moments of everyday life and turns them into something equally poetic. But mostly their art is very alive. There is a lightness in the work of both artists that betrays a deeper, more truthful reality. Like Tillmans, who once said that he makes photographs to enable him to really look, Tuttle has an equally strong belief in the power of the visual: “As a person, I simply need a good picture”.

The Critical Edge IV, 2015. Fabric, wood, nails, hand-sewn brown thread; four black MDF panels and four fabric elements 42" x 12' 1" x 3" (106.7 cm x 368.3 cm x 7.6 cm)

© Richard Tuttle, courtesy The Pace Gallery

In Tuttle's show, ‘Critical Edge’ refers to boundaries. Formally, as both embroidery and the cloth’s overlapping edges function as drawn lines. But also conceptually, as boundaries between the real and the abstracted, between the tactile sensation of handling each piece of fabric and the contemplative effect of the works viewed as a whole. The last room in Tillmans' Tate exhibition is also about boundaries, albeit in a more literal way. At one end of the room are two large seascapes, almost abstract. On the opposite wall is a visually arresting photograph of pieces of stacked wood, deep turquoise against a background of a beach. On closer look, this last image turns out to be the wreckage of the ship that sank whilst transporting immigrants to the Italian Island of Lampedusa.

Wolfgang Tillmans poses in front of his works Transient 2, 2015 and Tag/Nacht II, 2010. Courtesy Tate Photography

And this is where Tillmans goes one step further than Tuttle, by inserting socio-political comment into his poetry. Lampedusa makes us aware of our current climate, in which boundaries are paramount, and crossing them may bring danger and death.

In comparison Tillmans' seascapes are beautifully calm. For a short moment, they made me think that there might well be a future in which we can overcome boundaries, a day when ‘borders’ might mean no more than the edge between sea, sky and clouds. A world where hatred, fear and separation are surpassed by something closer to Richard Tuttle’s “Love, Truth and Freedom”.

Wolfgang Tillmans, 2017, Tate Modern until 11th June 2017

Wolfgang Tillmans will curate an artist-selected exhibition at Camden Arts Centre, 26 January – 15 April 2018

Richard Tuttle, My Birthday Puzzle, Modern Art London, until 13th May 2017

Richard Tuttle, The Critical Edge, Pace Gallery London, 13th April until 13th May 2017

Richard Tuttle, Solo Exhibition, De Hallen Haarlem, The Netherlands, until 7 May 2017